I was adding to my list of prior art for my ArabicBASIC project last week when I encountered a new-to-me project which implements a Javascript-like language in Pakistan’s national language, Urdu. This immediately caught my attention because Urdu is traditionally written in a modified Arabic alphabet.

This language is appropriately called UrduScript and it runs on NodeJS. I’m always interested in the tech stack of interpreters and compilers, but that’s not what we’re here to talk about.

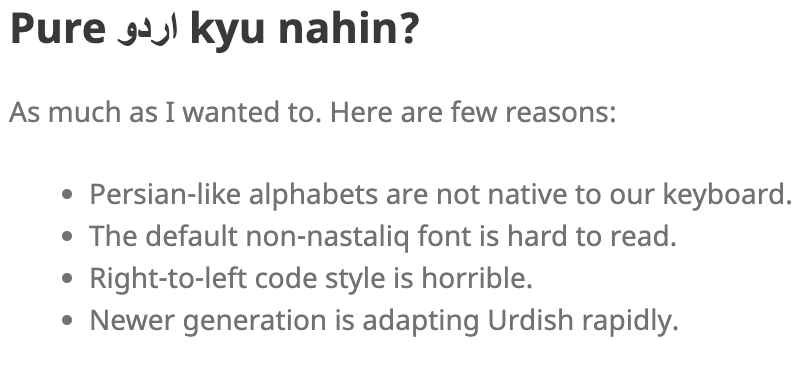

I must dissent from the author’s assertions about a very significant feature: the UrduScript interpreter only accepts code in the Latin alphabet. Now, the keywords are actually Urdu in terms of vocabulary and grammar; I am pretty familiar with Urdu’s grammar and linguistics, I just can’t speak it well. My in-laws readily confirm this. In any case, the author has much to say about it, recognizing that many will question this design decision:

The heading asks, “Why not pure Urdu”, by which he means Urdu as it’s typically written in Pakistan, in a modified Arabic alphabet that’s centuries old. And, as a former linguist, I just can’t agree with his reasoning.

#1: He has a point with this one: Indeed, modern laptops especially do not come with built-in Arabic, Persian (also written in a modified Arabic script) nor Urdu keyboards. I myself use a plastic keyboard overlay which is compatible with MacOS’ foreign alphabet settings. These are readily available on Amazon and such.

#2: Maybe for some individuals the local fonts are hard to read, but this is really a font problem which should not unduly affect language design. And I don’t accept the original assertion, either: I think the local fonts are in general quite nice. True, some are fugly but fonts are a choice, not destiny. This is not to support “enforcement” of a writing system, but norms are there for a reason and implementing UrduScript in Latin letters only will exclude some set of potential programmers. But, he redresses my critique in #4 below.

#3: Especially today and even in long lost days of 2017 when the project was originally written, right-to-left scripts are easily accommodated in modern software. Unicode is ubiquitous and we can consider Unicode the de-facto standard in computing.

#4: This is actually somewhat true; my wife confirms it as a native Urdu speaker herself. I am certainly aware that Latin letters were once widely used in SMS in the Arab world too, mostly when devices were not at all ready for Arabic script.

But, here we are in 2022 and with all due respect that era passed long ago. Even internet domain names can be in non-Latin script nowadays. Let’s move beyond script restrictions and open up the field so everyone can access programming immediately without first having to learn the Latin Alphabet. UrduScript achieved a notable goal in preventing potential programmers from having to know English before writing a single line of code by implementing keywords in Urdu. Let’s build upon that and not be held back.

Leave a comment